Lestock Métis wants RM of Kellross to return Red River Cart

Local Métis say the RM of Kellross is perpetuating historic harms by not returning cart. RM Councillor says it belongs to the RM.

This is a story about a Red River Cart, a well-known symbol of Métis Culture. The weathered cart sits beside the Welcome to Lestock Centennial sign, secured to the ground with rebar, unprotected from the elements. The Métis built this particular Red River cart in 2012 through grant money for the Métis, and it’s divided a community.

But this story is actually about much more than a cart. It’s about the history and struggle of the Métis in the area and the paternalism of the government. It’s about truth and reconciliation and a glimpse into the work yet to be done.

To tell you how this community became divided over a cart, we must start at the beginning.

History of the Métis Road Allowance people in RM of Kellross

If you open up the RM of Kellross’ webpage and go to the history tab, it will tell you where the area’s early settlers came from- Ontario, Central Europe, the British Isles, and Hungary. But one piece is missing, and it’s glaringly apparent. Nowhere does it speak of the Indigenous or Métis of the area.

The documentary “Ashes and Tears: The Green Lake Story” details the painful 1949 removal of Métis families from their homes on the RM of Kellross’ road allowance, known as “Little Chicago or the Chicago Line.” It was located approximately 8 miles out of Lestock, Saskatchewan. There were numerous other communities like Little Chicago across the prairie provinces.

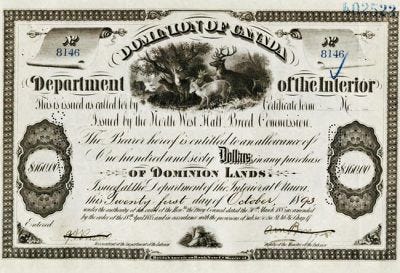

The Métis “squatted” on the road allowances because they had no land. To extinguish Indigenous land rights, generally speaking, the Federal Government offered First Nations people ‘treaty,’ and Métis were offered ‘scrip.’

Scrip was a certificate for 160 acres of land or $160 that could be exchanged for land. However, because the land was far away, people didn’t want to leave their communities, and land speculators seized an opportunity to take advantage of that. Speculators would offer a minuscule amount of money or something scrip holders needed, such as horses, in exchange for the scrip and would then sell it to the banks in Canada.

“Out of the 14,849 issued, land speculators ended up obtaining 12,560 money scrips. They also managed to leave the Métis with only one percent of the 138,320 acres of land scrip issued in Northwest Saskatchewan.” -The Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada

Fraud was rampant, with people’s names forged, showing they accepted scrip they never received.

Without any land, many made homes on unused crown land, like road allowances. Children on the road allowance weren’t allowed to attend school because their families didn’t own land and, therefore, didn’t pay school taxes. One of these road allowance communities was the Chicago Line; there were between 15 and 25 families who lived there.

In the ’40s, the provincial government took over Métis Farms, colonies set up by the Catholic Church.

“ The removal of the Road Allowance Métis was the last clearing on the Canadian plains of Indigenous people who lived freely on the traditional lands.” - Darren Préfontaine, researcher Gabriel Dumont Institute

In order to move the Metis off the road allowance, the RM coerced the families on the Chicago Line to leave with the promises of land, work and homes at the Métis Farms at Green Lake. Some said they were threatened with arrest if they didn’t go.

So the families left many of their belongings, pets, and livestock behind and loaded up what they were allowed onto a train headed to Green Lake, 49 km Northwest of Meadow Lake.

As the train pulled away, the people watched the smoke billow as their homes were burnt down, removing any possibility of returning to the road allowance, losing forever any possessions they left behind.

When they arrived at Green Lake, things would only get more challenging. Instead of improving their living situations, they faced severe hardships. There was no work. It was heavily treed bush, and there were no homes. Instead, they were given lumber to build houses, had to clear trees, and lived in tents. Very few made the first winter, leaving to return to the Lestock, Fort Qu’Appelle and Regina areas.

Darren Préfontaine is a Researcher in the Métis Culture and Heritage Department at the Gabriel Dumont Institute; he said, “The government policy was misguided. The provincial government was hoping that this would be a way to rehabilitate people who were having a hard go of it.”

“Now, the problem was it was very paternalistic. Nobody asked the Métis what they really wanted. The Métis probably would’ve preferred to have title to their own land in the Qu’Appelle valley and have, for lack of a better word, a Métis reserve, where all of the Métis people could live in one area, and they could access resources collectively in that area. But no one ever asked what they wanted. Government and municipal officials said, “Let’s just move the people off the land that they are from and put them several hundred kms northwest into the bush in an area that they are not familiar with and not provide them with all of the infrastructure that they would need to make a proper go of it. It just really wasn’t well thought out.”

Préfontaine explained that this was a “paternalistic” policy because officials thought that the Métis, as Indigenous people, could “just live off the land” because they were “one with nature.” "Well, people need infrastructure; they need to have homes before they can worry about making a living or trapping or farming. None of that was there. You’d be hard-pressed to take any settler from the region of Lestock and tell them ‘go to Green Lake’ and not have anything and see what you can do.”

There were serious long-term implications which can be seen today. Préfontaine said, “The Chicago Line/Lestock Road Allowance people endured the long-term trauma of a forced move. Some families were broken up, and there were hard feelings in the community when people returned from Green Lake. Community solidarity, which was really strong prior to the move, unravelled, and people, after coming back from Green Lake, gradually drifted to other parts of the province, most notably Regina. People suffered from low self-esteem and became even more distrustful of government. To this day, the relocation of the Chicago Line residents to Green Lake is a textbook example of government policy showing a “blatant disregard” for Métis people while having a deleterious impact upon them.”

In 2011, a historically accurate Red River Cart was Built by the Métis for the Métis with grant money for the Métis, but there was a catch…

“The Métis were responsible for the development of the versatile Red River cart used to transport goods over the prairie terrain. In effect, the Métis commercialized the buffalo hung with the invention of the Red River cart. Today, the Red River cart is one of the best-known symbols of Métis culture.” -Lawrence J. Barkwell, Coordinator of Métis Heritage and History Research at Louis Riel Institute

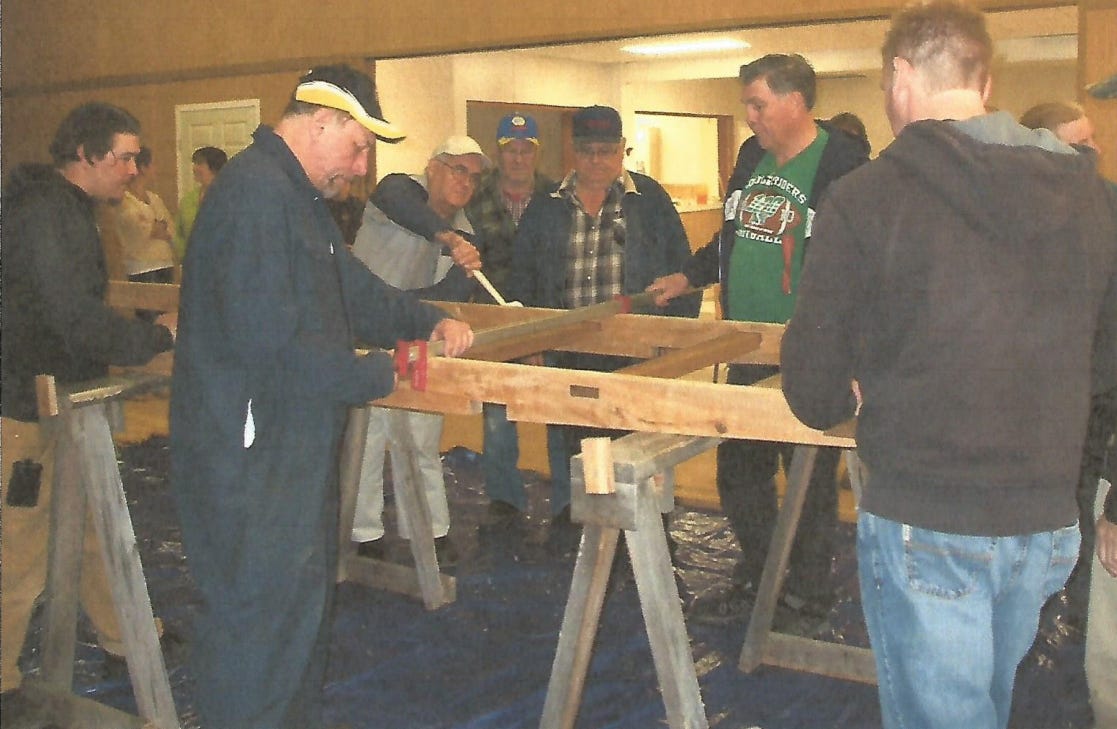

As part of the 2012 Lestock Centennial, the local Lestock Métis #8 wanted to access Provincial Grant money through Sask Culture/Sask Lotteries as part of the Métis Cultural Development Fund. The money would go towards contracting a Métis Master Cart builder in Manitoba who would build a historically correct Red River cart, bringing it unfinished to Lestock, where local Métis could learn the skill of their ancestors and finish the cart together.

However, because the Métis Local needed a legal entity number on the application, they approached the Village of Lestock, which agreed and partnered with them to apply. The President of the Métis Local was made the project leader and did all the work on the application for $5,159.60.

The grant was approved for all but $500, which the Métis group came up with. Armand Jerome of Jerome Cartworks brought the cart from his shop in Manitoba to the town hall in Lestock, where Métis’ hands worked to put on the finishing touches.

82-year-old Dwight Sabiston was one of the Métis men who worked on finishing the cart. He said the experience was great. “He included everybody. He left some of it undone when he brought it from Manitoba. We all got to do a little bit on it just to say that we did.” Sabiston got to work on the hubs. “There are wooden hubs on it, and they had big wood rasps. And we got to work them down to shape them…to fit inside the holes so the wheels would be able to turn. So we did that by hand.”

“It felt really good. Everybody really enjoyed that.”

The cart was on full display as part of the Centennial parade and celebration. After, it sat at the Métis Local’s President’s property for seven years.

In 2017, the Village of Lestock was absorbed by the RM of Kellross, and then in 2018, there was a change of leadership on the Métis Local, with Leebert Poitras taking over as President. As part of the transition, the council undertook efforts to retrieve the cart.

At some point, the cart was moved beside the Centennial sign. The RM said the former local President agreed with the move, and the Local says there is no motion of such an agreement in their minutes.

In July 2020, the Local wrote a letter to the RM explaining the cart's cultural significance, asking for it to be gifted back to them and proposing a new location for the cart's placement. The RM agreed, making a motion that said, “..the municipality would have no objections of the cart being moved only if it is on RM/ Property now.”

Because they didn’t have a place for the cart, they didn’t try to access it until August of 2022. The local emailed the RM, informing them they would remove the cart to use in their cultural event the next day and then leave it at the hall while they drew up a proposal about where they would like it placed in the community.

When they went to get the cart, it was secured with rebar, and they cut it free. A video shows a tense altercation between RM Councillor Kelly Komodowski arguing with the Metis local and then appearing to block them from taking the cart. Kelly Komodowski served as the former mayor and councillor of Lestock. He became an RM Councillor in 2020.

Despite the altercation, the cart was used for the Métis Cultural days celebration the following day. After it was over, they left the cart chained to the hall. However, the local said the RM told them to put the cart in the old fire hall for safekeeping. Then council made a motion to put it back at the sign, securing it again with rebar.

The following year, in 2023, the Métis Local tried again to get the cart for their Métis celebration. They sent a letter to the RM and President Leebert Poitras appeared as a delegation at an RM council meeting to speak with them.

“I wanted to see if we could get our cart back and put it on our own property. And they kinda refused me. They said no, it belongs to the RM because they took all of the assets of the town. If you want to put it anywhere, it has to be on the RM property. I mean, what could I do? The thing is, we own it… but legally, they don’t want to give it back to us.”

Poitras said the Reeve told him, “You have no rights to claim the Red River cart as your own importance as Métis people; everybody used the Red River cart back in the old days.”

The RM ultimately denied their request to use the cart, making a motion that said, “..the Red River Cart is in place, and there is no decision left regarding the cart; thus, no more discussion is necessary.”

They had their Metis Cultural Days celebration that year without the cart and applied for another grant to build a monument and have another less expensive cart built, which they had in place this year.

What does the RM say?

Despite several attempts to speak with Reeve Thad Trefiak, he has yet to respond.

However, I spoke with the former Mayor of Lestock and current RM Councillor Kelly Komodowski. He said the land where the cart sits is his, and because the RM retained all the assets from the Village of Lestock, the RM owns the cart.

When I first contacted him about the cart, he was upset. He said of the Métis Local, “They are nothing but trouble, that bunch.”

He said of the cart, “It wasn’t theirs to begin with…They have a cart out on their Métis land out here…so what are they worried about? They have a cart.”

When I asked about the Métis feeling like they are being further victimized, he responded, “That’s how they always are.” He said, “The cart is there as far as it looks; it belongs to the community because Lestock had signed everything to get the grant for [the former Métis President] to help her to get it for the Centennial, and it stays there.”

He said he wasn’t interested in returning the cart because it belonged to the RM.

I asked Komodowski if he understood why the Métis feel they are continuing to be harmed by the RM and the relationship of the RM to the removal of their people from RM land. “It’s significant to everybody. They are not the only ones that used the Red River Cart. Everybody that crossed Canada used the Red River cart through the west here as a way of travelling back then. It’s not only theirs. Other white people have used that to go across.”

When asked if the RM would return the cart in the spirit of truth and reconciliation or if they would continue to refuse, he responded, “I imagine so because it belongs to the RM.”

Komodowski said he was aware of what happened to the Métis years ago. “That’s unfortunate that happened, but that was before my time, and I’m not dealing with that right now. I’m dealing with the cart here.”

Aside from wanting the cart returned, the local is concerned about its deterioration because it has a regular maintenance schedule.

One thing that everyone seems to agree with is the community is divided over the cart. Dwight Sabiston said he’s happy about the new cart, and while he would like to turn his back on the uproar over the other cart, getting back the one he helped build would be nice. However, he doesn’t think they have a chance. “It would alleviate a lot of bad feelings. It might not get rid of it, but it might be a step in reconciliation.”

Leebert Poitras would like to see the RM council educated on the history of the Métis, their hardships, and Truth and Reconciliation.

Despite having a new cart, Poitras acknowledged it would likely take a lawyer they couldn’t afford to get it back. “It’s a matter of principle,” he said.